Cellular Physiology

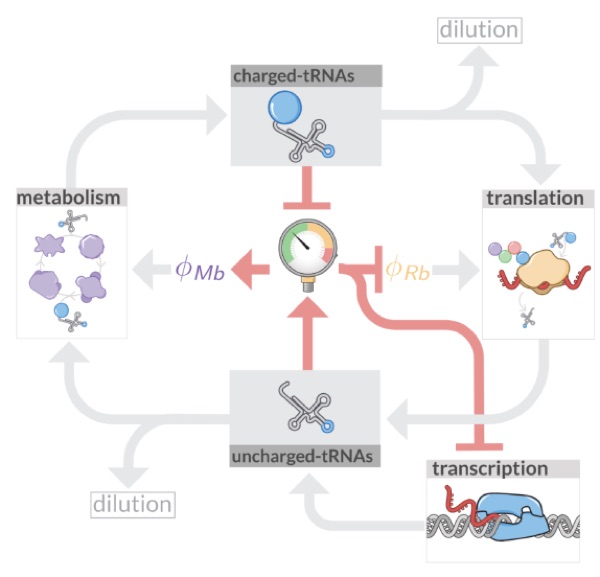

Effective coordination of cellular processes — such as division, motility, and metabolism — is critical to ensure the competitive growth of microbes. Pivotal to this coordination is the appropriate allocation of cellular resources between protein synthesis (e.g., growth) the metabolism needed to sustain it. But how can a cell – which is not much more than a watery bag of proteins – make such a decision? As a postdoc, I developed and experimentally tested mathematical models which provided one solution: cells encode a biochemical feedback loop which controls when (and where) proteins are made in response to how much energy is being generated via metabolism. This regulatory system imposes interesting constraints on how fast cells can grow, how fast they can adapt to changing conditions, and what different physical shapes cells can adopt.